Overview

|

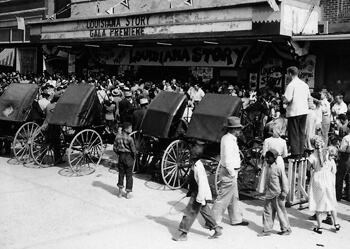

| Elemore Morgan, Sr., Gala opening of Louisiana Story, Abbeville, Louisiana, 1948. |

In 2006, a group of students at Louisiana State University created short films revisiting the people and places of documentary maker Robert Flaherty's Louisiana Story. Through short film and essay, "Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story" examines both the legacy of Flaherty's 1948 film and the experience of these student filmmakers in southern Louisiana. Suchy and Catano explore reflexivity in documentary filmmaking, depictions of the oil industry and the environment in south Louisiana, and the role of documentary images in making Louisianan identities.

"Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story" was selected for the 2009 Southern Spaces series "Documentary Expression and the American South," a collection of innovative, interdisciplinary scholarship about documentary work and original documentary projects that engage with regions and places in the US South.

Introduction

James V. Catano

Lush wilderness in a remote bayou and the exploratory genius of oil drilling technology; traditional ways of living and the intrusions of modern life; natural wealth and mechanical power—Robert Flaherty found these in abundance as he created his vision of Louisiana in the documentary classic Louisiana Story. The making of that Louisiana story follows Flaherty's standard format. He created "narrative documentaries," what we might call today "docudramas." But while Louisiana Story was scripted and its shots often staged, Flaherty wasn't merely re-staging events, nor was he only recording reality. In 1948 he was engaging in American mythmaking, joining "exotic" southern Louisiana, with its romanticized Cajun dwellers, to the corporate engineering marvel of mid-century oil exploration and extraction.

For the United States growing into its role as a world power, and Europe struggling to recover from the devastation of the Second World War, Flaherty's vision of natural beauty and mechanical progress was an endorsement of the elegance of the traditions of the past and the possibilities of the future. Flaherty took his own engineering marvel—the movie camera—and turned it upon the natural beauty of southern Louisiana to create this vision, framed as the story of a young Cajun boy. He sensed that everything was about to change—and the film leaves the significance of that change as an open question.

Sponsored by Standard Oil, Louisiana Story can be read as a tone poem as well as a story of an idealized Cajun culture coming to terms with the advancing oil industry in the region, a lyrical expression filtered through its hero, a young boy played by a Cajun Flaherty "discovered"—J. C. Boudreaux. As with his first film, Nanook of the North (1921), Flaherty worked with indigenous "non-actor" performers who played versions of themselves, restaging activities like hunting and fishing, as well as interacting with newly-arrived representatives of modernization who were in reality already established in the area. Flaherty's work recovers or depicts ways of life that were vanishing, while it exoticizes Flaherty's native "others"—in this case the Cajuns of southern Louisiana.

Descended from eighteenth century French exiles of Acadia, Nova Scotia, the Acadians (Cajuns) were forced from their homes and the country, with a large contingent eventually settling in southern Louisiana. There they encountered—and intermixed with—other peoples of the southern Louisiana frontier. In Alan Lomax's particular history of the culture, "The Cajun country was settled by French speakers from Canada, and they absorbed and Cajunized their local Indian neighbors and the settlers who came later on from various parts of Europe and from Africa and the West Indies. Out of this mix came a new culture, with its own cuisine, and its own music." Lomax's description occurs in his documentary, Cajun Country, where his specific goal is to discuss the concept of "Cajun" not as a group of people so much as a cultural dynamic capable of absorbing and reworking a variety of influences, albeit most of them deriving from traditional folkways found in southern France.1Cajun Country, dir. Alan Lomax (Media Generation: 1991). A streaming version of this documentary may be viewed at http://www.folkstreams.net/film,125. For more on the complex and ongoing study and discussion of what constitutes, Creole, Cajun, and the cultural Creolization of southern Louisiana see Nicholas R. Spitzer, "Monde Créole: The Cultural World of French Louisiana Creoles and the Creolization of World Cultures," The Journal of American Folklore 116:459 (2003): 57-72.

That goal is apparent throughout Cajun Country, and nowhere more so than in Lomax's discussion of Mardi Gras and its musical events: "Here's a true cultural marriage for you. The song is French, the gumbo is African, the costumes are French, and the sound comes from the Cajun variant of the African hot wind and percussion orchestra; the typical Zydeco combo of accordion and frottoir or washboard playing hot licks to what might be an old African chant." When set against Louisiana Story, such a discussion makes clear that Flaherty's film is an aestheticized evocation of a rural, white, male culture on the verge of transformation.

Louisiana Story's documentary 'argument' about what it means to be Cajun is romanticized, but that admission merits contextualization. At the time of Flaherty's filming, the term "Cajun" was used pejoratively, connoting backwardness and ignorance.2Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2003): 86-87. Seen in this context, Flaherty's romantic vision attempts to offset then-current attitudes and prejudices. Nor does Louisiana Story falsify the basic situation facing all streams shaping Cajun culture, among which Lomax lists French, African American, and Native American. The culture was primarily rural and under significant economic stress. While Flaherty romanticizes living conditions in Acadiana and the arrival of big oil, residents were not unaware of what oil drilling could mean for them economically. In Cajun Country, Felix Richard makes that clear in responding to a question by Lomax about the impact of oil: "Oh my god that's it. If it hadn't been for that we'd be starving just like they're doing in Mississippi right now." But if Richard recognizes that impact, he also notices in hindsight that it doesn't come without a price. As he says, the coming of big oil "kind of destroyed some of that [culture]."3In our interview with J. C. Boudreaux, he expressed similar mixed sentiments about the benefits and costs of the modernization of Acadiana, as does Carl Brasseaux, Director for the Center of Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in an interview included in one of the Revisiting student projects.

Flaherty can be challenged for failing to anticipate what was arriving with the oil industry. Indeed it is in some ways deeply ironic that a filmmaker whose work so regularly emphasizes what is being lost in a culture should here celebrate the arrival of the new without suggesting its possible impact. That romanticization of the future may be more troubling than his romanticization of the past.

Likewise, there is no question that Flaherty's choice to emphasize the white, French strain of rural south Louisianan culture is problematic. Where Lomax attempted to open out his 1991 documentary essay to include diverse culture streams, Flaherty chose to limit his scope to achieve his storytelling goals—whether it be that of a nuclear family or a particular cultural activity. As a result, Flaherty again left himself open to charges of romanticization that regularly appear in discussions of his work.4For their part Ellis and McLane choose to argue that classicism rather than romanticism is the best was to characterize Flaherty's work. New History of Documentary Film (NY: Continuum, 2008). In order to create the narrative frame central to his documentary mode, and to celebrate the exotic landscape he found in the bayou country, Flaherty did not make room to account for the complex dynamic that makes up Cajun culture.

Today, Cajun and Creole south Louisiana continues to draw visitors, artists, and scientists. Oil remains key to the area's economy. Half a century later, the region has undergone dramatic changes wrought by accelerated oil production, interstate highways, coastal erosion, petrochemical pollution, cultural "Americanization," tourism, media representations, and natural and human disasters. Yet the power of Flaherty's filmmaking is still visible in those physical aspects of the Louisiana landscape that are still recognizable. It is visible in the cultural practices that are shared across continuing racial and ethnic barriers, and it is visible in his influence on the makers of the videos of our project.

Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story documents our encounters with Flaherty's terrain, both inside his film and in the locations he visited in 1946-48. Using Flaherty's film for its framework, this video project engages several inheritors of Flaherty's vision, students of this state, as it presents different "takes" on themes raised in Louisiana Story that continue today: Louisiana's natural beauty and resources, its cultural heritage, and the costs and benefits of economic development.

The project used digital video in the context of historical and artistic research to engage Louisiana State University student filmmakers in a pedagogical and personal experiment. We were learning to perform acts of documentary in the doing of them. This work was guided by documentarian Rob Rombout, along with Professors Patricia Suchy, James Catano, and Adelaide Russo, and included students from a variety of disciplines.

Six videos inspired by Louisiana Story are excerpted here, along with student interviews about their documentary experiences. In addition, short essays discuss the conditions and implications of this experiment. These works are supplemented by multi-media materials and links to resources for further thinking about Flaherty, documentary forms, and southern Louisiana.

Revisiting Louisiana's Stories Through Student Interviews and Videos

James V. Catano

Revisiting Subjectivity in the Video Essay

One goal of Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story was to consider the work of student videographers in light of the discussion of identity and performance raised by Michael Renov's The Subject of Documentary.5Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). Students were interested in and influenced by Flaherty's vision of Louisiana, but they were also interested in "their" or "our" Louisiana as compared with Flaherty's. In their videos, students claim subjective positions while referencing, and in some cases critiquing, Flaherty's Louisiana Story. This combined emphasis echoes Renov's sense of documentary as coupling a dual impulse: "an outward gaze upon the world—with an equally forceful reflex of self-interrogation."6Ibid., 105.

In Revisiting, a wide variety of self-inscriptions, from mimetic critique to autobiographical expression, results from the students' taking up Renov's spectrum at points of their own choosing. The results are multiple takes on Flaherty as well as on southern Louisiana. For example, "Still/Immobile" revisits Flaherty's romantic vision of a lush and fertile Louisiana through an evocation of Richard Leacock's cinematography, while "Trompe-l'OeIL" critiques Flaherty's vision of a benign oil industry by incorporating his film into its discussion and visually contradicting it.

Along with their romanticized settings, Flaherty's films tend to represent tightly knit, often isolated groups. As Ellis and McLane note, "The dramatis personae of the Flaherty films are the nuclear family structured along conventional lines."7Jack C. Ellis and Betsy A. McLane, A New History of Documentary Film, (NY: Continuum, 2008): 18. Those limited, familial group dynamics occur within Flaherty's production techniques as well. Along with the subjects, Flaherty's "family and crew members screened and discussed the uncut footage with him. But final decisions about what to include were always made by Flaherty."8Ibid., 21. Co-produced by his wife Frances, and often sharing crew members, the resulting films nevertheless bear Flaherty's strong personal stamp.

Revisiting's student performances and multiple points of view somewhat burst this singularity, eschewing Flaherty's regular glance backward for immediacy and a wider social context. The student crew on this documentary were an ethnically, racially, and socially diverse group with roots that begin in Louisiana's Acadiana, then range outward to northern Louisiana, Mississippi, and include students from India and Asia. The students were as interested in what they could view through Flaherty's and their own camera lenses as in what they could analyze.

The students' work demonstrates the influence and impact of Flaherty in three particular ways. First, Louisiana Story's portraiture caught their attention and stirred a desire to achieve Flaherty's and Leacock's aesthetic fullness. Second, each video accepts as its starting point the basic sense of Acadians that Flaherty offered: the traditional homogenizing view of the Cajuns as direct descendents of the diasporic flight of French colonists banished from Nova Scotia to resettle in southern Louisiana. This rendering, as noted in the Introduction, overlooks complexities of ethnicity and race that characterize the region. Finally the stance taken by these videos aligns with Flaherty in expressing the voice of the videographer.

These student videos attempt a level of presence and expression that Bazin, writing several decades before Renov, characterized as the "essay film," having as its unifying feature an honest and directly expressed subjectivity—as opposed to a simplifying vision of documentary as recorded reality with commentary attached.9André Bazin, "Lettre de Sibérie, un style nouveau L'Essai documenté,'" France Observateur. 1958. Reprinted as "Bazin on Marker," trans. Dave Kehr, Film Comment 39:4 (2003): 44-45. In discussing Chris Marker's Letter from Siberia as an essay film, Bazin declares that the word "essay [is to be] understood in the same sense that it has in literature—an essay at once historical and political, written by a poet as well." For the students who made the videos in Revisiting, the goal was not to dismiss objectivity but to achieve an appropriate subjective voice.

That goal is further emphasized here in the formal presentation of the student videos. Each student section contains

- the performance of the student before the camera as interviewee and

- the performance of the student behind the camera (as well as before it in several of the student videos).

We meet the student videographers as interviewees who discuss the subjects and themes of their projects. Most are Louisiana natives with academic fields of study ranging from creative writing to kinesiology to photography, none with a background in documentary, and some who had never operated a video camera. All were sensitive to documentary's construction of authenticity. These interviews are directed by Rob Rombout, who sets up the shots and asks the questions out of frame. In response, students struggle with variations of role-playing and authenticity.

That struggle is humorously apparent in the interview of Linda Shkreli and Lauren Hendrix with its visible directorial hands echoing the off-camera order to "Look here," and "Get up." But its full complexities are enunciated by Marty Garner and Layla Soileau, where Marty is asked to shoulder the burden of his authentic "Cajun" heritage by speaking French. Midway through, Marty breaks into English, announcing that he wishes to perform adequately to the subject he is portraying. That self-performance returns in his and Layla's video segment, with its detailing of the students' lives. Taken all together, the student projects offer voices, styles, and themes to convey a sense of belief and believability in revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story—and their Louisiana.

Student Videos and Interviews

"Still/Immobile 6 Minutes"

Richard Leacock's cinematography and the notion of portraiture in documentary drew strong responses from our two photography majors. Challenged by our guest artist, Rob Rombout, to create a video response to Louisiana Story using only still photography, they also took cues from Flaherty's juxtapositions of natural landscape with man-made technology.

"Evangeline"

A team of creative writing and English majors, both of whom come from Cajun families, are the authors of this video. Their project was designed to address a desire from the director for representation of the French influence in Cajun culture. They interviewed their families and focused on how Cajun French figured (or failed to figure) in their families' daily lives. The title, borrowed directly from Longfellows's Tale of Arcadie, refers paradoxically to what the video's authors felt were the romantic excesses and exoticism of Cajuns in both Flaherty and Longfellow, as well as to touristic representations of "quaint" Cajun life that have capitalized on Longfellow's imagery.

"The Art of Depicting Scenery"

This video is a portrait of Elemore Morgan Jr., widely acknowledged as the foremost contemporary Louisiana landscape painter. Our students were inspired by landscape in Flaherty's film, and also fascinated by the regional landscape that is missing from Louisiana Story, the coastal prairie land that Morgan paints. We had originally been in contact with Morgan because of his connection to the Flaherty film and his long friendship with J. C. Boudreaux, but our students found in him a fascinating subject in and of himself. Morgan died suddenly in 2008.

"Punchline"

This video attempts to let representatives of Cajun culture speak for themselves, often humorously, as the title suggests. It uses interviews as its main structural device, along with the handmade items associated with the speakers. The building in back of the winemaker is the theatre in which Louisiana Story originally premiered.

"My/Mon Louisiana Story"

One of the most heavily scripted pieces, this video also provides the most autobiographical representation of what Louisiana "means" to its videographers. It also makes use of interviews and common cultural objects or motifs to establish its relation to the idea of Cajun.

"Trompe de l'OeIL"

This video is the most direct comment on and partial critique of Flaherty's vision of the benefits to be brought by the oil industry. It achieves its commentary through direct use of Flaherty's own work followed by a restructuring of that footage with their own. The narration is provided in both pieces by McIlhenny Company archivist and Cajun historian Shane K. Bernard's reading of an original manuscript of the screenplay of Louisiana Story. One of the students who made this film now works in the petroleum industry as an engineer.

Flaherty, Documentary, and Authentic Performances

Patricia A. Suchy

Often proclaimed the founding father of American narrative documentary, Robert Flaherty made his first film, Nanook of the North, in 1921. He continued making documentaries for another 27 years, including Moana: A Romance of the Golden Age (1926) and Man of Aran (1934). Louisiana Story was his last film, and many critics mark it as his best, with stunning cinematography by Richard Leacock, skillful editing by Helen van Dongen, award-winning score by Virgil Thomson, and script by Robert Flaherty and Francis Flaherty. Standard Oil's sponsorship of the film remains controversial in contemporary times, since Flaherty's view of the petrochemical industry's ability to co-exist with nature and culture in Acadiana seems to render it a benign force. Nowadays the changing landscape, coastal erosion, health problems, and environmental and cultural impacts of the industry on the region are hard to overlook. It is difficult to watch the film without "backshadowing" those effects, and for many, its artistic genius is compromised by its failure to indict, or even to predict, those harms. Others may object to Flaherty's failure to attend to the diversity and complexity of race and ethnicity in southern Louisiana. But as we revisit Flaherty's Louisiana Story, we weigh its merits and deficiencies in terms of the kind of documentary performance Flaherty was making.

Flaherty's method involved staging, or, more precisely, re-staging, the reality he observed. He documents phenomena that are already disappearing, ways of life that are threatened or transformed via industrialization, through what became known as "the Flaherty method": immersion in a place and among peoples, the crafting of narrative out of long, patient looking through a lens whose powers for Flaherty were spiritual. In perhaps a failure to understand that Flaherty is not documenting contemporaneous life, but rather something more like what Della Pollock has called "preserving the vanishing," some viewers and critics are troubled by Flaherty's method of re-staging events, be they Nanook's walrus or J.C. Boudreaux's alligator hunts.10Della Pollock, "Making History Go." Exceptional Spaces: Essays in Performance and History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998): 11. Yet to object to Flaherty's films on the grounds that he was "faking it" is in some ways to buy into the false dichotomy that pits artistic performance against documentary, to suggest that art somehow makes reality false, and moreover that there is a recoverable pure, real, true, direct way of going about documentary that eschews performance. It is also to circumscribe the goal of the documentarian to locating some sort of truth that is "out there," apart from what she might wish to perform or express.

Stella Bruzzi suggests ways to revisit Flaherty's "deformations" when she argues that "[t]he role performance plays in documentary has become [ . . . ] a critical way of establishing its credibility. [. . .] What emerges is a new definition of authenticity, one that eschews the traditional adherence to an observation or Bazin-dependent idea of the transparency of film and replaces this with a performative exchange between subjects, filmmakers/apparatus and spectators."11Stella Bruzzi, New Documentary: A Critical Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2000): 6. When our own company of students and faculty set out to revisit Flaherty, we began by thinking of documentary as performance. One of our goals was to cast the student filmmakers as documentarians so that they could study what was required of such a performance. Our revisiting of Flaherty's film was designed to explore the notion of "performative exchange"; we wanted to shift focus from the documentary mandate to "get it right"—or the truth claim as accurate, authentic, or "real"—to questions about how bodies are manipulating technology in performing authenticity, reality—or for that matter, irony, metonymy, synecdoche.12Brian Rusted, "Re: Visiting Flaherty," Critical review of Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story. Unpublished ms.: Proceedings of the Performance Studies International Conference, Aug. 2008. Forthcoming in Liminalities (http://liminalities.net/). The term "authenticity," a sticky wicket in documentary theory and criticism, was therefore revisited and redefined in our project—as it is for Bruzzi—away from issues of accuracy of representation in a documentary to issues of performance. In this sense we revisited not just Flaherty's sites, but also something of his methods.

In the sixty years since Louisiana Story, just as the landscape has changed and not changed, so have the kinds of performances documentarians make. For Flaherty, the performance was backstage, and during production of Louisiana Story, as in Nanook, he encouraged performers to contribute to the filmmaking process. The constructed narrative that results from this participation may not produce a film that is overtly self-conscious or reflexive in the ways that most of our student filmmakers' works are. But all performances are not reflexive, and, notwithstanding Jay Ruby's call for ethnographic film to be so, Flaherty does draw upon his subjects in ways that self-consciously engage performance via a working philosophy that is more closely linked to our project than it might seem from the apparent contrasts.

Following Ruby's work on Nanook, we would argue that Louisiana Story presents a more complexly subjective and co-constructed view of Acadian life than may be readily apparent from the film's generally modernist, auteurist style.13Jay Ruby, Picturing Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000): 67-93. See also Ruby's "A Re-examination of the Early Career of Robert J. Flaherty", Quarterly Review of Film Studies 5.4 (1980): 431-457. Flaherty was decidedly not a slavish follower of a shooting script. He encouraged his performers to view rushes as they came back from the lab (or, in Nanook, were developed on-site, with the film's performers sharing the labor of film processing). The screening of rushes while on location in remote sites was no easy task, and had Flaherty been less interested in making the film alongside his subjects, it would not have been necessary. In like fashion, he would famously abandon a day's production schedule in order to shoot a scene that particularly caught his eye or captivated him. The ensuing beauty of the cinematography in Louisiana Story, coupled with documentary expectations of objective truth, may distract viewers from looking at it with a sense of basic film communication. For example, many of the shots are subjective, from the boy's point of view or eyeline match. Flaherty's documentary work thus does not perform the so-called objective gaze; it reshapes reality poetically, and with collaboration from his performers.

Like Flaherty's film, our project concerns region and culture, but more significantly, it is about the documentary process itself. In order to affect this reflexivity, we scripted the expository frame that describes the terms of our project, and whenever possible we shot video of the students at work. We also determined that the unity in our film would come from its consideration of the documentary process, rather than from its depiction of region or culture. Revisiting's six student films present multiple, partial dialogues prompted by Flaherty's film and its environment, sixty years later. Following Flaherty's method, we screened rushes on location. The resulting overlap in the students' ideas and films comes from their borrowing of each others' footage, bits of sound, etc., and from working closely and intensely together.

Watching our student filmmakers at work provided a way to reread Flaherty's method of documentary through what Mikhail Bakhtin describes as "polyphony." We invoke this concept as a way to re-visit not just Flaherty's working methods, but also as a basis for learning with our students about documentary authorship ethics. These lessons were learned in the field as we explored together how a filmmaker performs documentary.

Polyphonic composition (in Bakhtin's sense, related to, but not the same as, musical polyphony) expresses an ethical encounter between author and hero. The polyphonic author relinquishes as much of her "surplus of meaning" as possible and engages her characters in a dialogue, rather than subduing them to her monologic control. The author "retains [. . .] only that indispensable minimum of pragmatic, purely information-bearing 'surplus' necessary to carry forward the story."14Mikhail M. Bakhtin, Problems in Dostoevsky's Poetics, trans. and ed. Caryl Emerson, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984): 73. In describing this authorial position, Gary Saul Morson and Caryl Emerson rely upon performance metaphors: the author and his characters may disagree, even though "it is the author himself who sets the stage for these contests he is not foreordained to win and the outcome of which he does not foresee." The author "plays two roles" in the polyphonic text, director and actor.15Gary Saul Morson and Caryl Emerson, Mikhail Bakhtin: Creation of a Prosaics, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990): 239. "It is as if the author could pick the hour and room for a dialogic encounter with a character," Morson and Emerson conclude, "but once he himself had entered that room, he would have to address the character as an equal."16Ibid, 242. A similar process is at work in many documentaries, where meaning outcomes are directly related to who controls the apparatus or the means of production: who holds the camera and edits the film. Polyphonic authorship in a documentary would entail that the person(s) holding the camera and editing the film be as fully responsive to the subjects of the documentary as possible, and to keep in balance the "two roles" a documentarian plays.

In Flaherty's works, he is both director and social actor. Too often, the critic erases or misconceives this role, focusing instead on the directorial choices, that is, reading the film like a finished text.17Rusted, op cit. We wish to thank Brian Rusted for his enthusiasm for our project and for his work on understanding documentary as performance, especially his notion of the potential in "reintroducing the performing body" into reading documentary and moving away from the "textual orientation" to documentary practices that has predominated in the history of its theory and criticism. But to revisit Flaherty in the manner of our project was to re-experience, materially and bodily, some of what he experienced as a social actor making a documentary in the field, engaging its other social actors in their environments.

If one thing emerges from the diary that Helen van Dongen kept while editing Louisiana Story (on location in a screened-in porch in the Abbeville house the Flaherty company rented) it is that the "story" of the film's title emerged through a long process of shooting, screening, discussion, re-shooting, discarding, arguing, shooting some more, screening some more, and so on. At one point van Dongen describes this process as "suffering through every foot of film, grasping our way through a maze of possibilities."18Helen van Dongen, "Filming Robert Flaherty's Louisiana Story," The Helen van Dongen Diary, ed. Eva Orbanz (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998): 43. Flaherty began with a script, but its audience at first was primarily the Standard Oil funders and various others like the McIlhenny family on Avery Island who also lent their support to the film.19Robert Flaherty and Francis Flaherty, Working Title Louisiana Story. Filmscript. Undated. Avery Island, Louisiana: McIlhenny Co. Archives. We thank Shane K. Bernard, Curator of the McIlhenny Archives and scholar of Cajun history and culture, for his generous assistance with this project. Of a later draft, van Dongen complains that the "[s]cript is written beautifully, but very often just as one would tell a story. When it comes to breaking it down in such a fashion that you can see how the sequences run, and plan how they should be shot, one finds many discrepancies."20Van Dongen, op cit., 31. Ultimately the script went through many rewrites to reflect what had been shot, what had been decided, what twists and turns the company took as they navigated the "maze of possibilities" and responded to exigencies in the environment, characters, and the story itself, which in some ways began to tell the company how it must be told—though not without considerable struggles. The Flaherty crew's work may not neatly be called polyphonic, but revisiting their process reveals that Louisiana Story's authorship—and indeed "the Flaherty method"—is close enough to make it a useful theoretical construct with which to think about Flaherty's works. Polyphonic authorship is an intersubjective ideal, rare and difficult to sustain. What Bakhtin would call "the gravitation toward" or the attempt to perform authorship this way is what matters most.

In Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story, our student filmmakers literally "play two roles" as producers and subjects. The six numbered student films in our project both re-visit and re-cover aspects of Flaherty's polyphonic performance. They are much more reflexive than was Flaherty, but this was a goal of the project, inspired by critics like Jay Ruby: to put methods, institutions, and performances on view alongside their objects of study.21Ruby, op cit., 151-180; 239-279. Revisiting allowed us to recover not just Flaherty's subjects, landscapes, and themes, but also his philosophy and method of performing documentary, with reflexive differences. The project has led us to rethink aspects of Flaherty's methods to argue for the centrality of performance to documentary generally, and not, as Nichols has characterized it, as a recent or "post-modern" development.22Bill Nichols, Blurred Boundaries (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995): 92-106. To be sure, Nichols' modes of documentary representation are not meant to be strictly chronological, but the concluding section of this chapter of Blurred Boundaries especially aligns the performative mode with the "paradigm shift" of post-modernity (105-06).

Inauthentic Performances: Cajuns of the Teche

When we revisited Avery Island, where many of Louisiana Story's sequences—especially those involving alligators—were shot, Shane K. Bernard, scholar of Cajun culture and history and curator of the McIlhenny Company's archives, shared some digitized copies of documentary and ephemeral footage he had located as he sorted through piles of materials, papers, and artifacts of the long history of the McIlhenny family's tenure on the island. Among the materials he unearthed was a Columbia Pictures Corporation short dated 1942 and entitled Cajuns of the Teche, one of a series called, on the first title card, "André de LaVarre's 'Quaint Folks.'"23André de LaVarre's 'Quaint Folks': Cajuns of the Teche, Columbia Pictures, 1942. The spelling of LaVarre's name varies from film to film made over his long career as travel and sports photographer and filmmaker; information about him may be found at http://www.burtonholmes.org/associates/andredelavarre.html. Although it contains glaring inaccuracies and blind spots (plantation houses, for instance, were rarely the homes of Cajuns, and the entire slave economy of such homes is never mentioned), we offer a sample of it here by way of contemporaneous contrast with Flaherty's work and because, on its surface, the confident voice-over narration with images that are meant to illustrate what the narrator says amounts to what most would understand as documentary. If this is documentary (and not simply bad documentary, but an offshoot of the travelogue and in some ways the legacy of Merian C. Cooper-style exoticism or what Erik Barnouw terms "explorer" or "primitive-people films"—ironically inspired by the success of Flaherty's Nanook),24Erik Barnouw, Documentary: A History of the Non-fiction Film, second revised edition, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993): 48-51. then Flaherty was clearly taking another set of paths to understanding the "Quaint Folks" of Acadiana.

In contrast to Flaherty's characters, the "Quaint Folks" of LaVarre's Columbia film are anonymous and typified; the voice-over narrator claims "We are Cajuns" in his first utterance (with no trace of anything whatsoever Cajun in his speech—and since we never see him, this utterance is clearly meant to speak "for" the folks pictured, who say nothing). In Cajuns of the Teche we witness performances of Cajun-ness (women spinning, quilting, braiding corn shucks and caning chairs; men trapping and fishing and farming; couples dancing; a saint's day procession and a wedding) and we are meant to understand that the narrator and his visual prosthesis, the camera, is an objective viewer and reporter of these performances. The role of the director as social actor here is minimized; any trace of his performance is confined to the title cards and the authoritative discourse of his agents, the narrator and camera. So too, the interactions of the Cajuns with the documentarist are minimized—nobody looks at the camera; nobody's gaze guides the camera as with Flaherty's point of view and eyeline match shots. Clearly, performance in this film is performance of a different order than in Louisiana Story, and detractors of Flaherty who find his re-staging of Cajun life problematic would do well to observe how inauthentic the results of merely observing performances are in Cajuns of the Teche. In sum, it is the styling of performances, the performance of the acts of documentary and not the performances documented, that matter most in the quest for authenticity in documentary performance.

Re-storying Louisiana

Patricia A. Suchy

I first saw Flaherty's Louisiana Story when I was a child, sometime around 1968. On Saturday afternoons at St. Pius X primary school in the Chicago suburbs parents could deposit their children in the gymnasium, where we would sit on the floor on gym mats and watch movies, mostly Disney educational films. The image of the boy hero of Louisiana Story paddling his pirogue—whom I did not then dream I would meet as a man, some forty years later—stayed with me. When I thought of Louisiana, I thought of those images: the boy in the swamp, his pet raccoon, the scary alligator, strange dark primeval fluids tapped with mysterious and powerful machines and welling up from below. Years later, when I was offered a job in Louisiana, I dredged up enough of the memory to consider that I was going someplace a little terrifying—a little exotic. I confess I liked that.

Most of what I see day to day in southern Louisiana is not exotic and only terrifying in ordinary ways: strip malls and cookie-cutter housing developments. And yet again, the year I arrived I acquired my own pirogue, made to order by a craftsman in Pierre Part, Louisiana.25Arnold Eagle, a photographer on assignment for Standard Oil to shoot production stills of Louisiana Story, befriended Flaherty and with his encouragement made the 1949 documentary short, The Pirogue Maker. The film features boatmaker Abdon Allemon, who is depicted making the pirogue used in Flaherty's film. It can be viewed on line at Folkstreams.net. Although a title on Eagle's film conjectures that "It may well have been the last pirogue made in Louisiana," there are, in fact, still a few practicing pirogue-makers. My pirogue was made by the late Raymond Sedotal, whose profile appears on Northwestern State University's Louisiana Folklife Center's website. If you venture into the Bluebonnet swamp in my pirogue, the sound of the nearby interstate traffic by the exit to the Mall of Louisiana dims, and you are in Louisiana Story before you know it: vultures roosting, hunched-over forebodingly; cypress trees stretching up out of the water in ways that remind me of people wading in or out; reptilian things gliding by the boat that sits very low in the water and does require balance. But also, since the nearest neighbor to my home across the river from Baton Rouge is a petrochemical plant, I am daily reminded of the ominous side of the oil industry romanticized in Flaherty's Thomas-Hart-Bentonesque drilling montage. It's an exquisite and thrilling sequence in the film, shot at night so that the machinery and the men's toiling bodies gleam with oil and sweat, cut to the cacophonous rhythmic beat of the rig. But drilling and channeling for oil exploration and transport in the Gulf Coast area have been directly responsible for the coastal wetlands loss that makes southern Louisiana so vulnerable to hurricanes, and the byproducts of oil refineries have made its citizens likewise vulnerable to petrochemical toxins and carcinogens.

In late August 2005 the images of Louisiana I carried in my head and body were forcibly changed, first by the hurricanes and then by what had to be done in the diasporic week that followed: the thrum of helicopters landing on the athletic fields at LSU for days and days, the piles of used clothing to be sorted, the flats of bottled water; the badly sunburned baby. Those images changed again when the power was restored and we came up for air long enough to turn on the television: people stranded on rooftops, aerial shots of mile after mile of houses in water up to their eaves; bloated bodies floating or propped up in wheelchairs outside the New Orleans Convention Center; looters, some of them wearing police uniforms, wheeling shopping carts through the flood. These are the lingering images I suspect most folks carry of southern Louisiana. Southern Louisianans speak of "before Katrina" and "after Katrina"; the media favor the term "in the wake."

It is far too easy, as I have done above, to draw direct lines between these newer, violent, sad images caught "in the wake"—genuinely terrifying in the starkest, most unromantic of ways—and Flaherty's images of the romance of petrochemical exploration and engineering. But Flaherty's works explicitly address how selected cultures live or struggle to survive within their unique natural environments, with emphasis on those environments that are already at risk or where great change has already begun to happen. Revisiting his Louisiana thus inevitably meant reconsidering yet again how what one of our subjects, the artist Elemore Morgan, Jr., called the "man-nature ratio" was working out.

When we set out to revisit Louisiana Story, however, it wasn't so much out of a rhetorical urge to correct Flaherty's vision as it was to re-envision our own context, which had been further ravaged by images spewing out of Fox and CNN. For a while, you couldn't swing a cat in New Orleans without hitting a documentary filmmaker carpetbagging images. The ultimate "post-Katrina" visual is a tracking shot obviously taken from a car window as it moves down a block of twisted, wrecked houses with spray paint hieroglyphics, uprooted trees, and overturned cars. I can't watch this shot any more both because I am overwhelmed by how much of this landscape still exists, and because it has made the whole sick vision strangely hypnotic and almost banal. How much longer do documentaries need to say "look how endlessly bad this is"? So for me, revisiting Flaherty's vision occurred "in the wake of" a seemingly endless stream of documentary images.

It may seem curious, therefore, that one doesn't hear much about the storms in our students' projects. Although most of our student filmmakers were directly impacted by Katrina and Rita, we didn't ask them to talk about the storms, nor did we discourage it. As is perhaps most evident in "Trompe de l'OeIL," the student video that deals most directly with the petroleum industry, then and now do not line up in direct opposition.

Revisiting is a complex set of tasks.

When we revisited with J. C. Boudreaux, we found him living in a FEMA trailer. His family's home in Cameron Parish was destroyed by Hurricane Rita. It's not the first time his family has lost everything in a hurricane. He's careful to weigh the blame for his family's predicament among bad or nonexistent environmental policy, the benefits economic development have brought to his beloved region, and everyday philosophy: c'est la vie. He still hunts alligators, but like Nanook and his walrus and the men of Aran and their sharks, he does not—and never did—hunt them in the way Flaherty stages. In many ways, Boudreaux's life did imitate the artful or typical life Flaherty co-constructed for him to lead in the film, but in more complex ways than the utter irony several critics of the film have pointed to with glee: as a young man he worked on oil rigs for several years and was glad to support his family with the income, but then switched to the less cinematically interesting (and for some critics, less symmetrically ironic) work of a telephone lineman because it paid better and was less dangerous. As for the untamed swamp through which he paddles and in which he hunts alligators in Louisiana Story, it looks about the same, because it still is, as it was when Ricky Leacock trained his Arriflex on it sixty years ago, a tourist attraction, a protected environment in the Jungle Gardens of Avery Island, across the road from the McIlhenny Tabasco Sauce factory. As a boy, Edward Simmons—the current president of those Jungle Gardens—was present for some of the shooting of Flaherty's film, and he attributes the successful preservation of the gardens' swamps, bayous, flora, and fauna to cooperative work with the oil industry.26Ned Simmons, interview by Patricia Suchy, Jim Catano, and Rob Rombout, Avery Island, LA, October 25, 2006.

I can make all kinds of excuses for Flaherty's romanticizing of Boudreaux's boyhood world, but it comes down to this: southern Louisiana's story, like any place's story, is not one story. The something rich and strange that wells up out of its swamps, prairies, and coastal marshes—and its FEMA trailer parks, petrochemical plants, and universities—can never be combined or reduced to a single vision. Reflexive about its partiality or not, one narrative will not suffice. But that was what Flaherty's aesthetic required.

Revisiting Flaherty's sites and subjects was also a physical journey, a set of embodied performances that allowed us to re-experience the region, and in some ways what our project documented is less the cultural and natural environment than it is our direct experience of it. One November morning, I found myself standing in a swamp on Avery Island, clutching a bag of batteries, wondering if we had sufficiently planned distribution of our video equipment for the late morning when our three vehicles would take off in three separate directions to interview various subjects. Another day, I found myself sweating in J. C. Boudreaux's FEMA trailer, the air conditioning turned off since it had been interfering with our audio recording, watching my laptop play back his young self waving at us from atop the "Christmas tree" that capped off the oil well in the final scene of Louisiana Story. Boudreaux was pleased to revisit the film with us that day. His only copy had been lost in the hurricane.

Flaherty famously said, "A film is the longest distance between two points."27Quoted in Paul Rotha, Robert J. Flaherty: A Biography, ed. Jay Ruby (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983): 5. He shot on location in southern Louisiana for over two years. He began with a script from which he kept getting distracted by the teeming life of the swamps and bayous. He'd rewrite and rewrite and shoot spider webs and in some ways it is a wonder the film was ever completed.

Although the project required a year of research in advance conducted by its producers, the Revisiting company's series of eight pre-production workshops, four days in the field, and less than a week in post-production predicted a much shorter distance. We wanted to exploit the potential of digital video technology—its rapidity, its accessibility, its potential to demystify the documentary enterprise. We imposed constraints—chief among these, time—since part of our experiment was to counter suppositions about documentary's sober, studied rhetoric. We imposed a deadline more familiar in live performance: at the end of the post-production week, we had a public screening, advertised well in advance so there was no turning back.

Since that screening we have fixed and fiddled with a few things, but most of the work occurred in that compressed time period. The result is a little "rough and ready," but we like that it's not perfect. At its heart is a learning process, and the works' textures express the trial and error necessary in such processes. The biggest surprise to us, watching it in the theatre after we had screened Flaherty's original, was that the student filmmakers are in many ways more like J. C. Boudreaux than they are like Flaherty. In Louisiana Story, a boy encounters a modern technology—the oil rig—is attracted to its power, and the encounter changes and does not change his way of life. Flaherty was well aware of the stakes of that encounter, but he had the tact or foresight or skill not to condemn or praise or even go too far in predicting the outcome of the modernization of Acadiana. That balances his romanticism a good deal. Our student filmmakers encounter a modern technology—digital video—and its power, and the encounter both changes the world they see and makes possible the seeing of it. In this encounter, the performance at the heart of our film, they are careful, thoughtful, insightful, sometimes frustrated, sometimes whimsical, but always aware, as was Flaherty, of the stakes of their encounters across the documentary camera.

Revisiting J. C. Boudreaux

In late summer 2006, the late artist Elemore Morgan Jr., who had long championed keeping the memory of Louisiana Story alive, introduced us to the hero of Flaherty's film. J. C. Boudreaux and his family had been living in Cameron Parish, but Hurricane Rita had taken their home away and they were living in a FEMA trailer on J.C.'s son's property near Sweet Lake. We interviewed Boudreaux there. Videography for the interview is by Shenid Bhayroo and Jenn Erdely, PhD students who worked as graduate assistants on the Revisiting project.

Credits

Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story was produced at Louisiana State University (LSU) in 2006-7. The video was shot on location in Louisiana in November, 2006, in Abbeville, Avery Island, Baton Rouge, Breaux Bridge, Broussard, Lafayette, Lake Martin, Maurice, Port Barre, and Scott, Louisiana.

The project was sponsored by the Program for the Study of Film and Media Arts, the Center for French and Francophone Studies, and the HopKins Black Box theatre in the Department of Communication Studies at LSU. Further support came from the Commissariat général aux Relations internationales de la Communauté Française de Belgique, the LSU Student Performing Arts Fee, and the College of Arts and Sciences.

Patricia A. Suchy, Producer & Writer

James V. Catano, Producer & Writer

Adelaide Russo, Producer

Rob Rombout, Director

Jenn Erdely, Assistant to the Producers and Director

Shenid Bhayroo, Director of Photography

Joey Watson, Co-Director of Photography and Equipment Manager

Jordy Wax, Editor

Trey Willard and Ben Powell, Sound

Reuben Mitchell, Narrator

Filmmakers:

Pierre Cazaubon, James Driscoll, Martin Garner, Mercer Hathorn, Lauren Hendrix, Sarah Jackson, Shital Patel, James Peck, Kenneth Reynolds, Linda Shkreli, Layla Soileau, Louis Toliver

Additional Production Assistance: Melodie Carbuccia, Penelope Dane, Catherine Tillson

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support and interest of The Bureau Wallonie-Bruxelles en Louisiane, Eliane DePues-Levaque (Permanent Representative); LSU's Centre d'études françaises et francophones, Bernard Cerquiglini, Director, and Todd Jacob, Assistant to the Director; Commissariat général aux Relations internationales de la Communauté Française de Belgique, Viciane Périn, Chef du Département Amérique du Nord and Didier De Leeuw, Assistant au Département Amérique du Nord; The HopKins Black Box theatre, Ruth Laurion Bowman, Managing Director and Lisa Flanagan, Theatre Manager; Elemore Morgan, Jr.; J. C. and Regina Boudreaux and family; Barry Jean Ancelet, Professor of French, University of Louisiana at Lafayette; Carl Brasseaux, Director, Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Louisiana at Lafayette; Wayne Parent, Professor of Political Science, LSU; Shane K. Bernard, PhD, Historian/Curator, McIlhenny Company; Edward Simmons, President, Avery Island Jungle Gardens; Lisa Grant, Assistant to Edward Simmons; The Flaherty/International Film Seminars, Inc.; McIlhenny Company; Avery Island Jungle Gardens; City of Abbeville, Louisiana; Vermilion Parish Library; Rocky and Lisa Sonnier; Bryan Champagne; Jackie Choate; Jeannie Comeaux; Jeremy Ferguson; Stephen David Beck ; Ginger Conrad; Sylvie Dubois; Lois Edmonds; Renee Edwards; Guillermo Ferreyra; Gary Hart; Lisa Landry; Michelle Massé; Anna Nardo; Margaret Parker; Robin Roberts; Ann Whitmer.

Recommended Resources

Documentaries

Cajun Country. Dir. Alan Lomax. Media Generation, 1991.

Focusing on music, food, and Mardi gras traditions, Lomax's film portrays the heterogenous "cultural gumbo" of southern Louisiana, attending to the ethnic mix that has come to be known as "Cajun" as well as to racial tensions and the effects of the petroleum industry and threats to Cajun French language in the history of the region and its peoples. It includes an interview with Barry Ancelet, who also appears in Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story. A streaming version of the video may be watched at http://www.folkstreams.net/film,125.

Louisiana Story (1948). Dir. Robert J. Flaherty. DVD NTSC. Home Vision Entertainment, 2003.

The film was restored for this edition, which includes several extras such as commentary by Frances Flaherty and Richard Leacock about the opening of the film, "Letters Home", in which Leacock reads aloud leters that he wrote to his wife while on location for the film, and an excerpt from The Land (1942), Flaherty's 1942 film made for the U. S. Department of Agriculture.

The Pirogue Maker (1949). Dir. Arnold Eagle. New Pacific Productions, 1992.

Eagle, a photographer on assignment to shoot production stills of Louisiana Story, made this short film that demonstrates the crafting of the pirogue that was used in Flaherty's film. Eagle was encouraged by Flaherty to make the film, and it is dedicated to him. A streaming video version of the film may be watched at http://www.folkstreams.net/film,188.

Cajun History and Culture:

Ancelet, Barry Jean. Cajun and Creole Folktales: The French Oral Tradition of South Louisiana. New York: Garland, 1994.

Ancelet, Barry Jean, Jay Edwards, and Glen Pitre. Cajun Country. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1991.

Bernard, Shane K. The Cajuns: Americanization of a People. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1993.

Brasseaux, Carl. The Founding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life in Louisiana, 1765-1803. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

Brasseaux, Carl. Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People, 1803-1877. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1992.

Rushton, William Faulkner. The Cajuns: From Acadia to Louisiana. New York: Farrar, 1979.

Flaherty and Louisiana Story

Barsam, Richard M. The Vision of Robert Flaherty: The Artist as Myth and Filmmaker. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Calder-Marshall, Arthur. The Innocent Eye: The Life of Robert J. Flaherty. New York: Penguin, 1970.

Custen, George F. "The (Re)framing of Robert Flaherty." Quarterly Review of Film Studies 7.1 (1982): 87-94.

Elliot, Keith. "A Boy of the Bayou Grows Up." The Humble Way 8.3 (1969): 16-19.

Flaherty, Frances H. The Odyssey of a Filmmaker: Robert Flaherty's Story. New York: Arno, 1972.

Flaherty, Robert Joseph and Frances Hubbard Flaherty. Robert and Frances Flaherty: A Documentary Life, 1883-1922. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005.

Grierson, John. "Flaherty as Innovator." Sight and Sound 21.2 (1951): 64-71.

Griffith, Richard. The World of Robert Flaherty. New York: Snell and Pearce, 1953.

Leacock, Richard. "In Defense of the Flaherty Traditions." Film Culture 19 (1996): 1-6.

May, Jennifer E. "A Louisiana Story: Searching for Jake's Cabin." The Daily Iberian 21 March 2004: C1+.

Morgan, Elemore Jr. and The Imperial Calcasieu Museum. "Louisiana Story: a photographic journey." Photography exhibit. Imperial Calcasieu Museum, Lake Charles, Louisiana. April 2004.

This exhibit has traveled to such locations as the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans (2006).

Orbanz, Eva, ed. Filming Robert Flaherty's Louisiana Story: The Helen van Dongen Diary. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998.

Rotha, Paul. Robert J. Flaherty: A Biography. Ed Jay Ruby. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983.

Ruby, Jay. Picturing Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Ruby, Jay. "A Re-examination of the Early Career of Robert J. Flaherty." Quarterly Review of Film Studies 5.4 (1980): 431-457. Also available online at http://astro.temple.edu/~ruby/ruby/flaherty.html.

Links and Online Publications

Abbeville, Louisiana's Giant Omelette Festival

http://www.giantomelette.org/.

Abbeville, Louisiana, where Flaherty's Louisiana Story company rented a large house while on location for the film, marks its French heritage annually with this festival, linked to several similar ones in France. This festival served as the background for many scenes in Revisiting.

Arthur Roger Gallery

http://arthurrogergallery.com/.

Avery Island, Louisiana

http://www.tabasco.com/avery-island/.

Famous as the home of Tabasco® Sauce, Avery Island is also the site of "Bird City" (a sanctuary for the snowy egret) and the Jungle Gardens, founded by E. A. McIlhenny in the 1890s. Many of Louisiana

Story's scenes were shot in this protected environment, and several of Avery Island's citizens recall the production.

Brasseaux, Ryan André. "The Backstory on Louisiana Story." Louisiana Cultural Vistas 20.1(2009): 20-29.

http://www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/leh/lcv-spring09/index.php?startid=5#/22.

Available here in an on-line edition, Louisiana Cultural Vistas is published by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Brasseaux's essay summarizes much of the available "backstage" material on Louisiana Story in print and packaged with the Home Vision Entertainment DVD release of the film in 2003.

Cajun Culture Resources at The Infography

http://www.infography.com/content//099234434822.html.

Lists several excellent print, documentary film, and Cajun music resources.

Center for Cultural and Eco-Tourism, University of Louisiana-Lafayette

http://ccet.louisiana.edu/index.html.

"Enhances cultural and eco-tourism in Louisiana through five avenues: its extensive online tourism guide, annual statewide tourism conference, interaction and research of its fellows, fieldwork and archives, and community outreach." Archives at the CCET focus on audio recordings; website contains a wealth of information and links to resources about culture in Louisiana.

Cinema on the Bayou

http://www.cinemaonthebayou.com/index.cfm.

Now entering its sixth year, "Cinema on the Bayou Film Festival is committed to advancing the understanding of Cajun and Creole cultures through film screenings, film panels and cultural exchanges among French Louisiana, the United States and the Francophone countries of the world."

Jay Ruby's Robert J. Flaherty Web Resources for Scholars

http://astro.temple.edu/~ruby/wava/Flaherty/index.html.

Jay Ruby, Professor Emeritus of anthropology at Temple University, has published several print essays and book chapters that critically re-evaluate Flaherty's works in terms of developing a set of methods (as well as an ethics) for producing ethnographic film. He is also the editor of Paul Rotha's biography of Flaherty. This page containing links to out-of-print texts about Flaherty focuses on Nanook of the North and is part of the Web Archive in Visual Anthropology.

Louisiana State University, Center for French and Francophone Studies

http://appl003.lsu.edu/artsci/cffsweb.nsf/index.

A co-sponsor of the Revisiting project, the Center supports interdisciplinary research and cultural initiatives that promote the French-speaking cultures of Louisiana.

Louisiana State University. Program for the Study of Film and Media Arts

http://www.lsu.edu/fma/FMA_home.html.

A co-sponsor of the Revisiting project, the Program provides an immersive approach to the study of film and media in special projects.

Louisiana Story at the Internet Movie Data Base

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0040550/.

Louisiana Story: The Reverse Angle

http://beta.lpb.org/index.php?/site/programs/ louisiana_story_the_reverse_angle/louisiana_story_the_reverse_angle.

Named the 2009 Humanities Documentary Film of the Year by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, and shot in the same time period in which Revisiting was made, this professionally-made film provides another kind of approach to "revisiting" Flaherty's work.

McNeese State University Library Archives and Special Collections Department, Historic Photographs of Southwest Louisiana: J. C. Boudreaux

http://www.louisianadigitallibrary.org/index.php.

This archive contains several digitized newspaper clippings about J. C. Boudreaux.

The Robert Flaherty Film Seminar

http://flahertyseminar.org/.

Founded by Frances Flaherty after Robert Flaherty's death, "The flaherty" is a non-profit organization that, among other activities, sponsors an annual Robert Flaherty Film Seminar and holds rights to archival materials.

The Robert and Frances Flaherty Study Center at Claremont

http://www.cst.edu/library/special-collections/robert-and-frances-flaherty/.

An archive of Flaherty materials including photographs, motion picture film, and audio recordings.

Robert Joseph Flaherty Papers 1884-1970, archive at Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library

http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/archival/collections/ldpd_4078765/ index.html.

Linked to the Center at Claremont, this archive of Flaherty materials focuses on print materials.

Rob Rombout

http://www.robrombout.com/.

Site of independent filmmaker who served as guest artist director for Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story.

Rotha, Paul. Robert J. Flaherty: A Biography. Ed. Jay Ruby. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1983.

http://astro.temple.edu/~ruby/wava/Flaherty/title.html.

The Rotha biography of Flaherty is out of print, but Jay Ruby has made the entire text available here.

University of Louisiana-Lafayette, Center for Louisiana Studies

http://cls.louisiana.edu/.

Two of the Center's scholars, Barry Jean Ancelet and Carl E. Brasseaux, are interviewed in Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story. The Center holds extensive archives and "seeks to plan, promote, and pursue programs of acquisition, research, and interpretation designed to provide scholars, students, and interested individuals with a better understanding of Louisiana's history and culture."

| 1. | Cajun Country, dir. Alan Lomax (Media Generation: 1991). A streaming version of this documentary may be viewed at http://www.folkstreams.net/film,125. For more on the complex and ongoing study and discussion of what constitutes, Creole, Cajun, and the cultural Creolization of southern Louisiana see Nicholas R. Spitzer, "Monde Créole: The Cultural World of French Louisiana Creoles and the Creolization of World Cultures," The Journal of American Folklore 116:459 (2003): 57-72. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Shane K. Bernard, The Cajuns: Americanization of a People (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2003): 86-87. |

| 3. | In our interview with J. C. Boudreaux, he expressed similar mixed sentiments about the benefits and costs of the modernization of Acadiana, as does Carl Brasseaux, Director for the Center of Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in an interview included in one of the Revisiting student projects. |

| 4. | For their part Ellis and McLane choose to argue that classicism rather than romanticism is the best was to characterize Flaherty's work. New History of Documentary Film (NY: Continuum, 2008). |

| 5. | Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). |

| 6. | Ibid., 105. |

| 7. | Jack C. Ellis and Betsy A. McLane, A New History of Documentary Film, (NY: Continuum, 2008): 18. |

| 8. | Ibid., 21. |

| 9. | André Bazin, "Lettre de Sibérie, un style nouveau L'Essai documenté,'" France Observateur. 1958. Reprinted as "Bazin on Marker," trans. Dave Kehr, Film Comment 39:4 (2003): 44-45. In discussing Chris Marker's Letter from Siberia as an essay film, Bazin declares that the word "essay [is to be] understood in the same sense that it has in literature—an essay at once historical and political, written by a poet as well." |

| 10. | Della Pollock, "Making History Go." Exceptional Spaces: Essays in Performance and History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998): 11. |

| 11. | Stella Bruzzi, New Documentary: A Critical Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2000): 6. |

| 12. | Brian Rusted, "Re: Visiting Flaherty," Critical review of Revisiting Flaherty's Louisiana Story. Unpublished ms.: Proceedings of the Performance Studies International Conference, Aug. 2008. Forthcoming in Liminalities (http://liminalities.net/). |

| 13. | Jay Ruby, Picturing Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000): 67-93. See also Ruby's "A Re-examination of the Early Career of Robert J. Flaherty", Quarterly Review of Film Studies 5.4 (1980): 431-457. |

| 14. | Mikhail M. Bakhtin, Problems in Dostoevsky's Poetics, trans. and ed. Caryl Emerson, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984): 73. |

| 15. | Gary Saul Morson and Caryl Emerson, Mikhail Bakhtin: Creation of a Prosaics, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990): 239. |

| 16. | Ibid, 242. |

| 17. | Rusted, op cit. We wish to thank Brian Rusted for his enthusiasm for our project and for his work on understanding documentary as performance, especially his notion of the potential in "reintroducing the performing body" into reading documentary and moving away from the "textual orientation" to documentary practices that has predominated in the history of its theory and criticism. |

| 18. | Helen van Dongen, "Filming Robert Flaherty's Louisiana Story," The Helen van Dongen Diary, ed. Eva Orbanz (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998): 43. |

| 19. | Robert Flaherty and Francis Flaherty, Working Title Louisiana Story. Filmscript. Undated. Avery Island, Louisiana: McIlhenny Co. Archives. We thank Shane K. Bernard, Curator of the McIlhenny Archives and scholar of Cajun history and culture, for his generous assistance with this project. |

| 20. | Van Dongen, op cit., 31. |

| 21. | Ruby, op cit., 151-180; 239-279. |

| 22. | Bill Nichols, Blurred Boundaries (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995): 92-106. To be sure, Nichols' modes of documentary representation are not meant to be strictly chronological, but the concluding section of this chapter of Blurred Boundaries especially aligns the performative mode with the "paradigm shift" of post-modernity (105-06). |

| 23. | André de LaVarre's 'Quaint Folks': Cajuns of the Teche, Columbia Pictures, 1942. The spelling of LaVarre's name varies from film to film made over his long career as travel and sports photographer and filmmaker; information about him may be found at http://www.burtonholmes.org/associates/andredelavarre.html. |

| 24. | Erik Barnouw, Documentary: A History of the Non-fiction Film, second revised edition, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993): 48-51. |

| 25. | Arnold Eagle, a photographer on assignment for Standard Oil to shoot production stills of Louisiana Story, befriended Flaherty and with his encouragement made the 1949 documentary short, The Pirogue Maker. The film features boatmaker Abdon Allemon, who is depicted making the pirogue used in Flaherty's film. It can be viewed on line at Folkstreams.net. Although a title on Eagle's film conjectures that "It may well have been the last pirogue made in Louisiana," there are, in fact, still a few practicing pirogue-makers. My pirogue was made by the late Raymond Sedotal, whose profile appears on Northwestern State University's Louisiana Folklife Center's website. |

| 26. | Ned Simmons, interview by Patricia Suchy, Jim Catano, and Rob Rombout, Avery Island, LA, October 25, 2006. |

| 27. | Quoted in Paul Rotha, Robert J. Flaherty: A Biography, ed. Jay Ruby (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983): 5. |